“Just as it now seems obvious that the differences once thought to exist between men and women either didn’t exist, or only existed because of the patriarchal culture of the time, and were no justification for not taking women seriously, one day it will be obvious to everyone that the differences currently thought to exist between adults and children either do not exist, or would not exist were we taking children seriously, and that they do not justify not taking children seriously.”

– Sarah Fitz-Claridge

Transcript of a talk given at the Oxford Karl Popper Society on 16th May, 2021

[I recommend watching the actual talk instead of reading this transcript. The transcript loses something. [youtube] [transcripción en español]

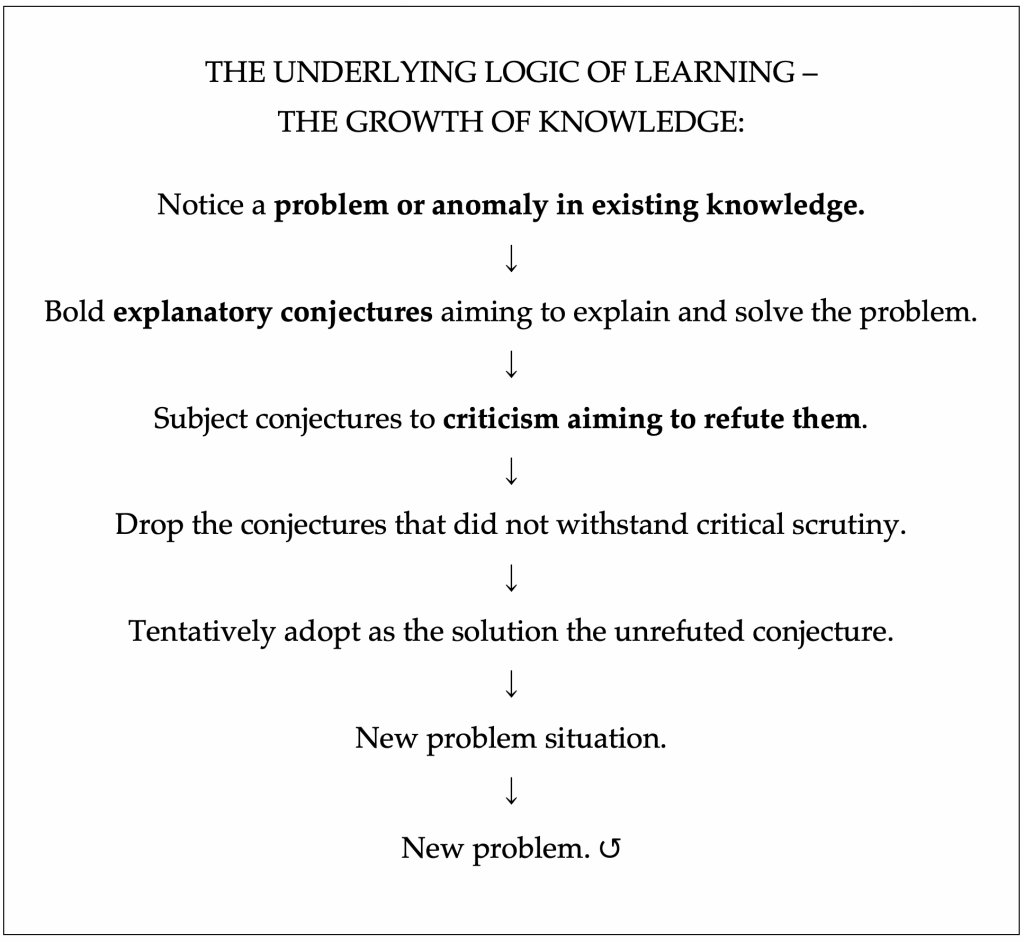

Taking Children Seriously is the only educational philosophy in existence that takes seriously the fact that human beings are both creative and also fallible. It is informed by Karl Popper’s epistemology.

Instead of viewing some sources of ideas—such as parents’ ideas—as having authority, Taking Children Seriously takes the growth of knowledge seriously, which means free competition of the ideas irrespective of source.

The most distinctive feature of Taking Children Seriously is the idea that children should have the same freedom, rights, respect and control over their lives as adults.

I do not mean that children should fend for themselves by the way: they very much need our love and protection, our care and attention, fun and play, and vast amounts of engagement with their ideas and interests. They are not born able to survive and thrive without us.

Why is it that when I say that children should be in control of their lives, people hear “children should be left to rot”? If you are being guided up a mountain by an expert mountaineer, and you are a novice, and I say “you should be in control of you own life”, would that imply that your mountaineer guide should leave you to rot halfway up the mountain? Of course not.

There is a huge anomaly between the Enlightenment ideas in our culture—what we think right for us adults—and what we think right for children.

We view children differently from how we view adults. [By “we” I mean our culture: just about everyone in the world has the prevailing/old view of children as opposed to the new view I advocate.]

My aim here is to highlight this difference in view, because once you see it—as I have discovered myself (recently!—and this is why I am particularly excited about this talk)—it can really open your eyes to blind spots in your thinking that you had no idea were there.

I am going to start where most people are in their thinking about children, but we will get to some less obvious issues later.

We are the adults; They are the children; and they need to stop ‘misbehaving’ and comply with our ‘requests’ or face the ‘consequences’—and we genuinely feel that this is for their own good.

Why do we call it ‘misbehaving’ when it is a child, but ‘disagreeing’ or a ‘conflict’ when it is an adult?

And why do we call it ‘having a tantrum’ when a child is upset, but when it is an adult we say we are struggling or ‘very frustrated’ or ‘at the end of our tether’?

Why do we still think in terms of correction and discipline when it comes to children, but if you were to read a book advising people about correction and discipline to coerce their spouses, you would be aghast.

If you were to follow such advice, you might find yourself being criminally prosecuted for coercive control too. The law—in England at least—recognises that it is not just domestic violence that is problematic, but also non-violent coercive control.

It recognises that in the case of adults, but the standards are applied differently in the case of children.

Why is that ok?

If a grown woman can’t tolerate being coercively controlled, how on earth can a defenceless child?!

Why is it ok for us to consider ourselves the authorities over our children?

We expect our children to ask our permission, and we are the authority over them deciding whether to grant permission—‘letting’ them do something—or to deny it—saying ‘no’ to them.

Yet we would never presume to impose such an authoritarian relationship on our friends or our spouse. We take our friends and spouses seriously. At least we do now.

There was a time when women were not taken seriously. It is not that they were seen as not human. They were seen as being a different kind of human—as being in a class of humans not quite having what it takes to be in charge of their own lives, and really needing, for their own good, to live under the benevolent patriarchal control of their father or husband.

Women were not allowed to vote, and married women were not allowed to own property, and working was seen as improper for married women. In 1933, my own grandmother lost the job she loved when she informed her boss that she was engaged to be married. It was thought perfectly proper to discriminate based on sex or the marital status of a woman.

Similarly, in America in the past, slavery was legal, but even long after it became illegal, many still viewed black people differently from how they viewed white people.

But whereas now most people take adults seriously as sovereign individuals irrespective of sex or race or marital status, almost no one takes children seriously.

We have dropped the paternalism with respect to women, but we have yet to drop the paternalism when it comes to children.

If you are objecting to my using the word paternalism given that it refers to the idea that certain people or groups need to be controlled in a fatherly way for their own good—how is it any less immoral to control children than it was to control women?

“Children are children, not adults!” I hear you say.

Many similarly ridiculed the idea of women being taken seriously because women are women, not men! It is a circular argument!

And just as it now seems obvious that the differences once thought to exist between men and women either didn’t exist, or only existed because of the patriarchal culture of the time, and were no justification for not taking women seriously, one day it will be obvious to everyone that the differences currently thought to exist between adults and children either do not exist, or would not exist were we taking children seriously, and that they do not justify not taking children seriously.

You may be thinking, “Children are dependent! Obviously we need to manage them for their own good!”

If so, do you apply that argument consistently?

Do you think that all those who are dependent do not have the right to be in control of their own affairs?

Do you think that a home-educating father with no income should not have control over his life because he is dependent on his partner’s income?

Do you think that a soldier loses his right to self-determination if he becomes dependent after losing three of his limbs in war?

Aren’t we all dependent in some way? Why single out children?

Let’s look at the difference in view with respect to making mistakes.

Everyone believes that adults should be free to make mistakes. We can point out the mistake, but if the person is not persuaded, she gets to do what she thinks best.

Even if the entire world could see that she is making a gargantuan mistake, we still take the view that it is her life, and that she gets to make her own decisions.

But when it comes to children, the prevailing view is that in their case, coercion is justified and good for them.

Why is it good for them but not for us?

If you say “coercion is justified because adults know more than children,” do you apply that argument consistently?

Do you say that those who know the most in the world would be justified in coercing the rest of us? Is that what should happen?

The standard way of viewing children is that they are not quite equal to us; they are not creative and rational like we are; they will not learn unless subjected to unwanted teaching.

In the standard view, the family is like a benevolent dictatorship. Or perhaps you prefer the idea that the parent is the captain of the ship, in which we, the parents, are responsible for steering the child-ship to avoid icebergs on her journey to adulthood. You might say that whilst some run a ‘tight ship’, and throw them in the brig—give them a ‘time out’—if they disobey, other parents are more ‘lenient’ and ‘give their children more leeway’. Either way, it is all viewing children through the same paternalism. ‘Giving children more leeway’ still assumes that it is for us the parents to decide how much leeway to give them. We are above our children, granting or withholding the leeway. We are still managing and steering them, granting our own ideas authority.

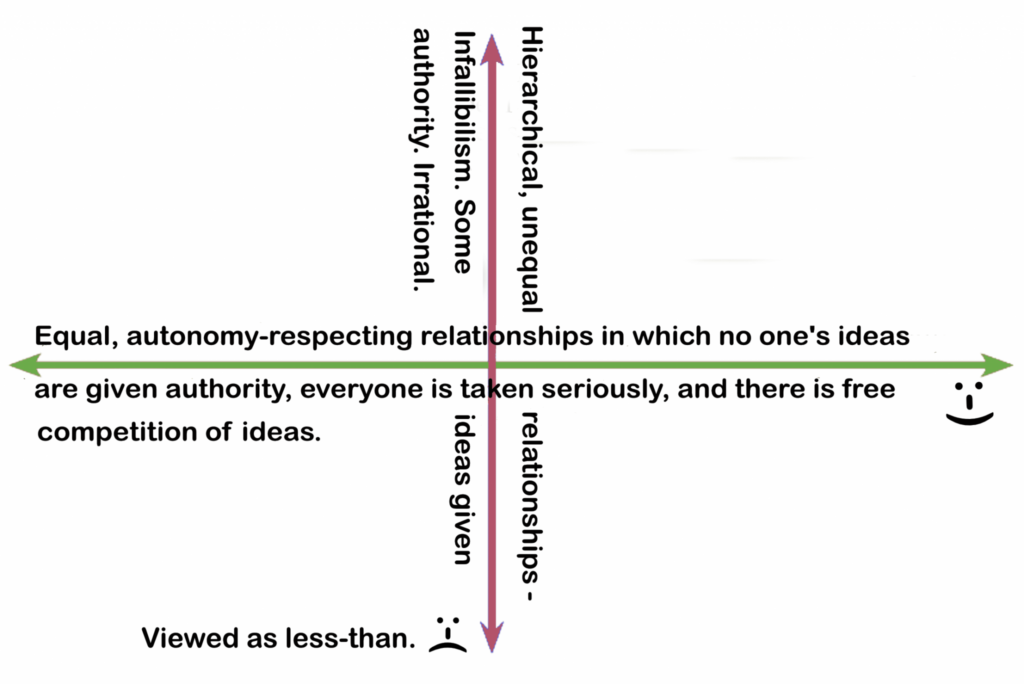

This view of children as being less-than, inferior, not quite equal to us creates an inherently authoritarian, hierarchical parent-child relationship that pits parents and children against each other—a top-down relationship in which the parents’ ideas are given authority, and the children are not free.

There is a reason we are free to manage our own affairs. There is a reason for the rights and freedoms we have—so as not to impede the growth of knowledge; and in previous societies that did not have those freedoms, the growth of knowledge was suppressed, and life was miserable for everyone. The Enlightenment arose out of the idea that that should not happen.

Hierarchical, top-down relationships informed by ‘we know best’ paternalism impede the growth of knowledge. That is true irrespective of sex or race—and it is true irrespective of age too.

So I propose that we drop the paternalism in favour of autonomy-respecting, side-by-side, equal relationships in which ideas can all compete freely irrespective of source, no one’s ideas have authority, and parents and children are on the same side.

It is not obvious why people leap to the startling conclusion that children are not noticing problems and creating at least as many explanatory conjectures as we are, and criticising them, and learning just like we do. That is, to the extent that we ourselves are creative and rational, so are they.

You may be thinking:

“What about babies?! They just cry all the time! I’m not seeing any evidence of babies being creative and rational!”

How do children ever become rational if they start out irrational?

People mistake the lack of knowledge of babies for a lack of rationality.

When babies are born, their knowledge and means of communicating is… limited. But contrary to what most of us imagine, babies’ pre-crying utterances are meaningful. When a young baby says “Neh!” she’s politely asking to be fed. And what do we do? Ignore her request until she’s screaming!

I myself have been known to scream when a polite request has been ignored.

Yet we declare babies irrational because of the way they express themselves.

How to express ourselves through pleasant, rational-sounding conversation is something we learn. It only seems obvious to us how to communicate through ‘rational conversation’ because we have created that knowledge.

If babies were not creative rational persons, they would be unable to learn to speak. Yet young children learn language whether anyone is teaching them or not. They are learning as many as 20 words per day. And that is just a tiny fraction of what they are learning. Even if we ignore everything else they are learning and just look at what they are learning in terms of language alone, they are learning the meanings of words, grammar, what we call things, when to use certain words, and when we shouldn’t be using such words; they are learning nuances, and the cultural significance of everything.

“That’s all well and good,” you may think, “but how can we have an equal relationship with a two-year-old child who knows so much less than we do?!”

It is not about how much each party knows, it is about the view you have, the theory you have of the relationship and the other person. And it is about how you view knowledge and the mind.

If you see the mind as being passive, like a bucket, and knowledge as being like a fluid that needs to be poured into the mind from above, you will be viewing children as being objects beneath you passively receiving the knowledge you think you are pouring in from above, and the relationship will necessarily be hierarchical.

Similarly, if you are a behaviourist, you’ll be manipulating the black-box mindless child-object using classical or operant conditioning.

That is treating the child’s thinking as if it does not exist, and your own thinking as being necessarily right.

If we are fallibilists, we are viewing others as equals, and ideas from all sources can compete freely instead of some sources’ ideas being deemed to have authority.

It is not about how much the different parties know. And it is also not about the overt form of the relationship:

You can have an autonomy-respecting, equal relationship with your boss or your employees or your child. It is the substance that matters—how you view the other person and interact with them—not the overt form.

You can have a hierarchical, non-equal relationship with someone who is nominally a peer, but whom you look down on and manipulate.

In equal, autonomy-respecting relationships informed by fallibilism, we are not viewing the other person as being beneath us or inferior to us. And we are viewing the life and choices of others as being a matter for them.

And we are so confident that the other person does not need to be managed or controlled, that it would not even occur to us to mention that confidence.

An author1 who brands parents who “don’t say no” “Jellyfish parents”—and advocates what she calls “backbone parents” who provide “consistency” and “firmness”—suggests saying to children: “I believe in you” and “I trust you,” which, she claims, are not coercive.

I disagree.

If you have ever been on the sharp end of this parenting strategy, you know that the carrot of “I trust you” is backed by the stick of “Do not disappoint me.”

What is the purpose of saying those things if they are not in doubt?

Doesn’t “I trust you,” usually mean “I don’t trust you as far as I can throw you. Show me I am wrong.”

And when we say “I believe in you”, sometimes we are trying to prop the lowly child up from above, suggesting a hierarchical relationship; or again, we are really saying “I don’t in any way believe in you. Please try not to embarrass me by being the utter failure I am expecting you to be.”

Praising and rewarding children is similarly coercive. They are an expression of superiority: evaluation from above. Judgement of the child’s performance. The goal of praise is to manipulate using operant conditioning. In effect, it denies the existence of the child as a person with a mind.

Would you say ‘Good job!’ to an adult you respect? No. You might say “thank you”, or you might express genuine respect or admiration, but you wouldn’t say “Good job!”

The ‘Good job!’ carrot is backed by the stick of a potential negative evaluation of your performance. Praise suggests a hierarchical, unequal, coercive relationship in a way that genuine expressions of admiration or gratitude do not.

The standard view of children embodies the false theory that “children do not have reasons like we do”; “the causes of their actions are outside their minds” or “they do not even have minds.”

But actually, they do have reasons—just like we do. And taking children seriously means engaging with their reasons, not discounting them.

The standard paternalistic view of children is so ubiquitous that it even appears in books by authors who think they are against coercion and manipulation.

So let’s look at some examples. I will be slightly rewording some of them to highlight the anomaly—the double standard in the standard view.

[Please note that the books I have chosen to quote from are the best books I could find, not the worst. All of them are worth reading.]

What would you think of this2 advice?:

“What if my wife refuses?” a husband asks. I respond that such a husband needs to understand that his wife isn’t used to having a husband who holds to a limit. Such a wife is likely to require longer to comply with a limit willingly. The husband simply needs to hold his ground by not leaving the space until the screen is either turned off or handed over.

Comply with a limit willingly? Gosh! If that’s ‘willingly’, I would hate to see ‘unwillingly’!

If that would be appalling treatment of an adult, what makes it unobjectionable to treat a child that way?

Here is an example of such an author failing to even consider that a child could have reasons for behaving in a way adults deem ‘challenging’:

“Some of the many causes of challenging behaviors are:

• unmet need for human connection

• unmet physical and/or emotional needs

• stress caused by a child’s emotional environment

• environmental conditions that compromise a child’s physical wellbeing

• physical and/or emotional sensitivities with which a child is born

• sensitivities that are part of a child’s innate temperament

• physical and/or emotional sensitivities or challenges caused by stresses during and following birth

• sensory processing challenges”

– Pam Leo, 2005, 2007, Connection Parenting: parenting through connection instead of coercion, through love instead of fear, second edition, p. 138

Where is: “there is a disagreement, and you are not listening”? Somehow that did not make it to the list.

What would you think of this3 advice?:

With husbands who are especially oppositional (and with almost all young men), it works much better to make a request if they’ve already said yes. In other words, you want a man to already be nodding (literally or figuratively) to ensure a greater chance that he’ll feel more naturally inclined to do what you ask. I generally ask wives to try to get the husband to nod or say “yes” three times before telling him to do something. This helps him feel connected and heard—and also predisposes him to do what you ask.

Would you like to be patronised and manipulated like that?

What if your husband forbade you from doing something and said this4:

“Sweetie, I don’t know whether I am right, but as a husband it is my job to make this decision. Some things are judgment calls. Do you agree that there are some things husbands need to make the decision about?” So long as the wife feels really listened to and understands it is a tough question for a husband and I am doing my best as a husband to keep my wife safe, even if she doesn’t like it, we will usually end up okay. We can’t always reach agreement but wives need to feel listened to and taken seriously.

Would that be taking you seriously? Would that be taking your ideas seriously? Would that be an equal relationship, or would that be giving his own ideas authority?

Is taking someone seriously just a matter of making them feel heard?

Is taking someone seriously consistent with managing and manipulating them? I do not think so. Here is another quotation:

“I am not so concerned with whether they make all the same choices or use the same strategies that I do, but with whether their actions and words and tone of voice make it clear that they take their kids seriously.”

– Alfie Kohn, 2005, Unconditional Parenting: moving from rewards and punishments to love and reason

It is all our choices, our strategies, what we ourselves think best. The child’s own wishes, reasons, thinking are barely even considered—as if the child does not even exist as a sovereign person with agency like we are.

Is it ok to coerce people as long as we ‘help’ them ‘process the emotions’ caused by our coercion?:

“Our adult ability to tolerate frustration takes root in our childhood. More precisely, it involves our parents’ ability to teach us how to handle the word ‘no’ and cope with our residual emotion. Most parents say the word ‘no’ but don’t help their children process the emotions around this.”

– Shefali Tsabary, 2010, The Conscious Parent

If your boyfriend said ‘no’ (for your own good), but offered to ‘help’ you ‘process the emotions around that’, would that be taking you seriously? Would that be an equal relationship in which everyone’s ideas are competing freely? Or would that be a coercive hierarchical relationship?

Under the heading, “Helping Kids with Big Emotions” this next quotation is about how to view and deal with what this author calls the ‘big emotions’ resulting from your coercion of your child.

“Welcome the upset. If you can respond to your child’s anger with compassion and a softening of your heart, he’s likely to cry. The more he cries, the better. The fear is locked in his body. He may thrash and sweat and want to push against something; that all helps his body let go of the fear. If he lashes out, move back so he can’t hurt you. […] Your job is to help him feel safe enough to get past the anger to the more vulnerable fear, grief, and powerlessness beneath.”

– Laura Markham, 2015, Peaceful Parent, Happy Siblings

What if it were a husband feeling entitled to coerce his wife? Would that be ok if he ‘helped’ his wife to “get past the anger” to the “fear, grief, and powerlessness” this author seems to find desirable?

‘Effective’

Another thing we find in books for parents viewing children through this lens of paternalism, through hierarchical coercive relationships, is lots of stuff about what the research says, what the studies say (allegedly), what is ‘effective’—instead of how is it right or wrong to treat someone?

“Evidence-based, science-based, data-driven parenting”

“The American College of Paediatricians warns that…”

“Over and over, research has demonstrated how detrimental manipulation and coercion are to a child’s sense of self and wellbeing.”

– Shefali Tsabary, 2013, Out of Control

If the ‘research’ said the opposite (and I am sure that you could find research saying the opposite, because people have their agendas when they are doing this ‘research’, and they can make it say anything), would that make it ok to manipulate and coerce people children?

We have a different view of children. [By “we” I mean people in general; our culture.] We have completely different standards for children. We look at what is effective, what the research allegedly says.

“Some adults insist that a good wallop never did them any harm, but the actual research suggests the opposite.”

– Lawrence J. Cohen, 2001, Playful Parenting

Does what the research allegedly says determine what is right? If it went the other way, would that make immoral behaviour moral?

Why do we call it “a good wallop” or “corporal punishment” when you hit a child, but “domestic violence” or “spousal abuse” when you hit your wife, or “assault” or “battery” when you hit your employee?

We have a different view of children. It is all about what is ‘effective’.

“No specific intervention, neither mine nor anyone else’s, is guaranteed to be effective. […] What I’ll be describing has a much better chance of success.”

– Alfie Kohn, 2005, Unconditional Parenting: moving from rewards and punishments to love and reason

Notice that it is about what ‘works’, what “strategies” are “effective”, to produce the desired product—as though children are lumps of clay awaiting our moulding—pragmatism—paternalism. It is not taking the child’s ideas seriously. It is not free competition of ideas irrespective of source.

“The key is to see what works best and then to manage the process to get the best results from your child.”

– Rick Capaldi, 21st Century Parenting

It is all, the child as product, the child as being below us, and we are crafting this child object.

There is a staggering amount of deceptive language in books aimed at parents.

Here is an example (some more paternalism):

“Maria Montessori, the groundbreaking educator, realised that when adults facilitate the proper environment, we can tap into children’s intrinsic desire to learn and be independent. […] And children are given some power. They are allowed to choose their work from a prescribed range of options.”

– Hunter Clarke-Fields, 2019, Raising Good Humans

This is not taking children seriously.

If you were allowed to ‘choose’ from a prescribed range of options, would that constitute giving you some power, or reducing your power?

How would you feel if your wife left a note on your dinner plate saying5:

“You can have your dinner after you have done the chores—and you can do your chores any time you like.”

And the authors5 recommending leaving such notes for children call it a ‘free choice’ for the child. The slave overseers of old likewise found it very effective to threaten to deny food, but at least they didn’t pretend to be increasing the slaves’ freedom of action!

This paternalistic view of children is all about what we ourselves think best—and calling it our child’s ‘free choice’. What the child thinks and wants are not part of the picture.

It is not taking them seriously.

Here is another example:

“When she is older, talk to your child about how you feel about screen time. You can use win-win problem solving to set healthy limits together.”

– Hunter Clarke-Fields, 2019, Raising Good Humans

No one who uses language decently would call that “win-win problem-solving”. And there is nothing together about that limit setting.

There is so much Orwellian language in books aimed at parents: so-called ‘requests’ that the child is not free to decline; so-called ‘agreements’ that the child hates; so-called ‘natural consequences’ that are anything but natural. It is all about how to get the child to obey, and using non-coercive-sounding words and the semblance of empathy to hide the coercive reality.

What would you think of this advice?:

If we establish a boundary that allows for no more than thirty minutes of screen time before it is time for our wife to iron our shirts, and our wife violates this, it is important to hold to the limit consistently, while at the same time showing empathy. There are a variety of ways to go about doing this. We can come to an agreement with our wife so that if she breaks the agreement she knows the screens will be removed from the equation until the ironing has been completed. If our wife pitches a fit, the husband stays resolute in his request that the screen be shut down or handed over. Holding firm on boundaries and limits doesn’t mean we use coercion or harshness, which can easily border on abuse. Instead, we help our wife engage the issue with a sense of joy and lightness.

Would that be good marriage advice? Why is it ok to double-bind a child that way, but not an adult?

Here is the actual quotation:

“If we establish a boundary that allows for no more than thirty minutes of screen time before it’s time to do homework, and our child violates this, it’s important to hold to the limit consistently, while at the same time showing empathy. There are a variety of ways to go about doing this. We can come to an agreement with our children […] so that if they break the agreement they know the screens will be removed from the equation until the homework has been completed. […] If a child pitches a fit, the parent stays resolute in their request that the screen be shut down or handed over. Holding firm on boundaries and limits doesn’t mean we use coercion or harshness, which can easily border on abuse. Instead, we help the child engage the issue with a sense of joy and lightness.”

– Shefali Tsabary, 2016, The Awakened Family

Notice that not only is the author advocating that the child be coerced to do the homework, and not only is she advocating that the parent coercively impose a 30-minute limit of so-called screen time, she also requires the child to pretend to have agreed to the coercive limits and rules, and to obey “with a sense of joy and lightness”.

Talk about double bind! It is brutal under the Zen veneer.

Forget about what children want. Forget about what children think. Forget about children having reasons. Instead, we are told by expert after expert, that the question to ask is:

“What do children need?”

– Hunter Clarke-Fields, 2019 Raising Good Humans

How about this6 marital advice to ignore your wife’s wishes in favour of what you think she needs:

Husbands often confuse meeting their wife’s needs with making her happy. Meeting your wife’s needs does not always make her happy. Women need to stick to a strict diet to remain slim and healthy. Being told that it is time to stop eating may not make them happy. Telling your wife she may eat that cake would make her happy, but it wouldn’t meet her ‘real’ need to have a husband who will support her in being slim and healthy. Meeting women’s needs sometimes means loving them enough to say no and set limits.

What does it mean to be a ‘real’ need that the person herself does not want?

And we are told that focusing on these alleged ‘needs’ is taking children seriously!:

“To focus on children’s needs, and to work with them to make sure their needs are met, constitutes a commitment to taking children seriously. […] A child’s preferences can’t always be accommodated, but they can always be considered and they need never be dismissed out of hand.”

– Alfie Kohn, 2005, Unconditional Parenting: moving from rewards and punishments to love and reason

And what do these authors think children need? Why teaching, of course:

“When a child does something inappropriate, [… it is] an opportunity for teaching[…] Moreover, to see children’s behaviour as a ‘teachable moment’ invites us to include them in the process of solving the problem, which is more likely to be effective.”

– Alfie Kohn, 2005, Unconditional Parenting: moving from rewards and punishments to love and reason

There is that word ‘effective’ again.

Would it be taking you seriously if your husband were thinking in terms of ‘teachable moments’ for you? Or would that be patronising, hierarchical, coercive relationship territory?

How about this7:

If our wife is having problems with a certain issue, such as being loud when we are on the telephone, that becomes our signal for what she needs to learn.

His wife’s problem?!

How would you feel if your husband were committed to ensuring that you learnt what he thinks you need to learn, and did not listen when you indicated that you were not interested? Would that be taking you seriously?8:

When my wife doesn’t show respect, it is a signal to me that we have more teaching to do. In this case I want to ask myself a few questions: […]

– ‘Does she understand what I expect about showing respect?’ […]

“Erin, is that showing respect?”

“I don’t know.”

“You’ve told me before that you don’t feel respected if somebody yells at you. What about if someone talks back to you?”

“I don’t know.”

“Would you like it if I talked back to you?”

“I don’t care.”

“Really? So you mean it is okay if I start talking back to you?”

“If that’s what turns you on.”

[…] [I was losing the will to live by this point. There was more. A lot more.]

Here, I am educating her a little more about some of the finer points of respect.

Incidentally, why do some parents call it “talking back” when it is a child, but “ expressing disagreement” or “free speech” when it is an adult?

Books for parents tend to be full of suggested questions embodying a paternalistic, pedagogical agenda. The idea is to ask children questions to ‘teach’ them things. But asking questions we know the answer to is testing our children, evaluating them, judging them from above.

Such suggested questions are all about channelling the child into our pedagogical agenda. Obviously we are thinking that it is for their own good. Nevertheless, we are not taking them seriously, we are steering them, moulding and shaping them. Hierarchical coercive relationships. Their own ideas are not relevant. Cannot be allowed to compete freely.

We should not be giving what Karl Popper called “unwanted answers to unasked questions”9—let alone unwanted questions to check their answers!

As I know from my own life, unsolicited advice can sometimes be “unwanted answers to unasked questions” and thus problematic.

If we are Popperians, we may view it as theory-sharing or helpful criticism—and wonder why it sometimes seems unwelcome.

Our intention is to be helpful, but advice-giving can be boundary-violating. It can come from a place of looking down on, a hierarchical relationship, and not having the boundless confidence in our child that we would have in our spouse or friend.

If there is a pattern of your ‘theory sharing’ being unwelcome, you may have a blind spot—like I did.

Consider seeking consent first—asking if your child would like to hear your theory/advice/criticism—before proceeding. It may be unwanted at that time.

And on the other hand, sometimes we fail to share theories also because we are not quite viewing the child as being equal to us, because we are viewing our child through the lens of paternalism. And that is problematic too.

Here is an example of a situation in which not sharing your theory would be a mistake:

Suppose I am going for a job interview, and am unaware of the smart professional dress code expected, and instead of wearing a conservative black suit, I am about to leave home dressed inappropriately for that job. I would really hope that my loved ones would tell me about the dress code—rather than viewing me as too delicate to hear that information—so that I wouldn’t fail to get the job just because I was wearing the wrong outfit.

We do need to offer our children all sorts of information—about dangers for example—and access to ideas and criticism that they might want to know about. People find that when they are taking their children seriously, they are trusted consultants to their children. Taking children seriously does not mean not sharing your theories. But it does mean being sensitive to whether or not the other person wants to hear your theory.

If there is a pattern of us being worried about our child, that is a lack confidence in the child. We may be seeing the child as being beneath us.

Do not imagine that our children do not sense our worry.

Whenever a problem with our children has become a bit of a pattern, that is a clue that something is off, that there may still be a touch of paternalism in our view, that we may still be interacting in a hierarchical relationship instead of a side-by-side equal one. Problems really are soluble. Is something blocking the solving of this one?

This can happen to all of us—we are all fallible human beings, and we do not necessarily have the knowledge, and we cannot always create it right then when we need it—we all make mistakes.

The sort of thing that can happen is if we inadvertently have a fixed idea of what a solution would look like. Instead of thinking laterally and creatively and questioning everything, and jointly solving the problem, we have an unexamined theory of what must happen, and are thinking in terms of how to get the child to feel all right with our ‘solution’.

That is not how we would approach problem-solving in an equal relationship, is it? It is just not quite right. Not quite a real solution. It is not quite allowing the ideas to compete freely. It is still thinking we know best.

Unequal, hierarchical relationships and paternalism can creep in even when we want very much to be taking our children seriously—as in my case—blind spots.

I myself continue to discover blind spots I have had with respect to taking children seriously—often. We all make mistakes. We are not omniscient. Knowledge has to be created, and we sometimes fail to create it in the moment. The truth is not manifest. We do not know infallibly how to take children seriously, we have theories about it, and we can be mistaken, and many of our ideas are likely to be mistaken. We are all fallible. That is the human condition.

But one thing I have found helpful is looking at this from the perspective of the difference in view. Am I inadvertently looking down on my child from above, hierarchical relationship style, viewing my child as being not quite equal, not quite a fully autonomous person? Do I have an agenda for them? Am I inadvertently or intentionally steering them—for their own good, of course, but still!

Taking Children Seriously means replacing hierarchical, paternalistic, ‘we know best’ relationships, with non-coercive, autonomy-respecting, side-by-side relationships in which all the ideas can compete freely irrespective of source.

Taking Children Seriously means taking ideas seriously. Not impeding the growth of knowledge.

And for the Popperians in the audience: taking ideas and the growth of knowledge seriously means taking children seriously too.

Just as it is obvious to us now that women and black people should be taken seriously, I do predict that one day it will be obvious to everyone that children should be taken seriously too.

Notes

1. Barbara Coloroso, 1994, Kids are worth it: giving your child the gift of inner discipline

2. Shefali Tsabary, 2016, The Awakened Family:

“‘What if my child refuses?’” a parent asks. I respond that such a parent needs to understand that their child isn’t used to having a parent who holds to a limit. Such a child is likely to require longer to comply with a limit willingly. The parent simply needs to hold their ground by not leaving the space until the screen is either turned off or handed over.”

– Shefali Tsabary, 2016, The Awakened Family, Chapter 21: From Discipline to Enlightened Boundaries, The Power of Clear Limits and Boundaries, p. 303

3. Susan Stiffelman, 2010, 2012, Parenting without power struggles:

“With kids who are especially oppositional (and with almost all teens), it works much better to make a request if they’ve already said yes. In other words, you want a child or teen to already be nodding (literally or figuratively) to ensure a greater chance that he’ll feel more naturally inclined to do what you ask. I generally ask parents to try to get the child to nod or say “yes” three times before telling him to do something. This helps him feel connected and heard, and also predisposes him to do what you ask.”

– Susan Stiffelman, 2010, 2012, Parenting without power struggles, Chapter 7: How to get kids to cooperate, pp. 143-144

4. Jack Pransky, Parenting from the heart:

“‘Sweetie, I don’t know whether I’m right, but as a parent it’s my job to make this decision. Some things are judgment calls. Do you agree that there are some things parents need to make the decision about?’ […] So long as the child feels really listened to and understands it’s a tough question for a parent and I’m doing my best as a parent to keep my child safe, […] even if she doesn’t like it, we will usually end up okay. [We] can’t always reach agreement but […] they need to feel listened to and taken seriously.”

– Jack Pransky, Parenting from the heart: a guide to the essence of parenting from the inside-out, 4th edition, 1997, 2012, Chapter VIII: Teaching kids what they need to learn

5. Unfortunately, although I think I remember the book from which I got this quotation (decades ago), I no longer own the book, and I have been unable to track it down to be sure, so I dare not name the book in case my memory is mistaken.

6. Pam Leo, 2005, 2007, Connection parenting: parenting through connection instead of coercion, through love instead of fear:

“[Parents] often confuse meeting children’s needs with making them happy.

What’s the difference between meeting children’s needs and making them happy? Meeting children’s needs does not always make them happy.

Children need to brush their teeth to have oral health. Being told that it’s time to brush their teeth may not make them happy. Telling children they can skip brushing their teeth would make them happy, but it wouldn’t meet their ‘real’ need to have a parent who will support them in having oral health. […]

Meeting children’s emotional needs sometimes means loving them enough to say no and set limits.”

– Pam Leo, 2005, 2007, Connection parenting: parenting through connection instead of coercion, through love instead of fear, Chapter 6: Connecting through the discipline of decoding children’s behavior, pp. 142-143

7. Jack Pransky, Parenting from the heart: a guide to the essence of parenting from the inside-out, 4th edition, 1997, 2012, Chapter VIII: Teaching kids what they need to learn:

“If a kid is having problems with a certain issue, such as being loud when the parent is on the telephone, that becomes our signal for what she needs to learn.”

– Jack Pransky, Parenting from the heart: a guide to the essence of parenting from the inside-out, 4th edition, 1997, 2012, Chapter VIII: Teaching kids what they need to learn

8. Jack Pransky, Parenting from the heart: a guide to the essence of parenting from the inside-out, 4th edition, 1997, 2012, Chapter VIII: Teaching kids what they need to learn:

“When [the child] does not show respect, it is a signal to me that we have more teaching to do. In this case I want to ask myself a few questions: […]

– ‘Does he understand what I expect about showing respect?’ […]

‘Eric, is that showing respect?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You’ve told me before that you don’t feel respected if somebody yells at you. What about if someone talks back to you?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Would you like it if I talked back to you?’

‘I don’t care.’

‘Really? So you mean it’s okay if I start talking back to you?’

‘If that’s what turns you on.’

[. . .]

Here, I’m educating him a little more about some of the finer points of respect.”

– Jack Pransky, Parenting from the heart: a guide to the essence of parenting from the inside-out, 4th edition, 1997, 2012, Chapter VIII: Teaching kids what they need to learn

9. Karl Popper, 1974, 1992, Unended Quest, p. 40

See also:

Sarah Fitz-Claridge, 2021, ‘Taking Children Seriously: a new view of children’, talk given at the Oxford Karl Popper Society, 16th May, 2021, https://takingchildrenseriously/taking-children-seriously-a-new-view-of-children/

This is outstandingly clear and concise. I feel as if I’ve just had a shampoo and blowout of my brain 🙂