“Even the junkiest of junk television can be superbly educational—by sparking questions and enjoyable conversations.”

– Sarah Fitz-Claridge

From the archives: Posted on 4th September 1997

When I see people saying that television is not educational, I feel saddened, or, if they are using their theory to justify denying or limiting access to it to their children, I feel appalled. It seems so sad that all those children are missing out on such an incredibly rich source of information, and that all those parents snootily eschew television-watching as “uneducational”. I think that a shameful attitude for any unschooler to hold. Those who advocate limiting or denying access say things like:

- “TV is not interactive”. True. TV is not interactive. Neither are books, or great works of art, or classic recordings of great opera.

- “Books are interactive, because you can interpret them differently each time”. That is just as true of TV. (But neither books nor TV are at all interactive even so.)

- “Reading books sparks conversations but TV doesn’t.” Rubbish. TV has much greater potential for sparking conversations because it provides vastly more information (in the wide sense) than the equivalent time spent reading. The reason TV doesn’t spark conversations in some families is to be found in the minds of the parents. It certainly does spark conversations in all the homes I myself visit. Watching television can be a communal activity giving rise to incredibly valuable conversations. And conversation is the most educational thing in the world. So TV-limiters are actually limiting something that gives rise to the most educational thing in the world.

- “The content of most TV programmes is bad/junk so I’ll just let my children watch quality programmes—educational programmes.” This coercion is an impediment to real education, just as making children conform to any other “educational” agenda would be. How is it that unschoolers can often articulate so beautifully why “educational coercion” is a mistake, but then fail to apply their excellent arguments to many areas of life to which logically those arguments do apply?

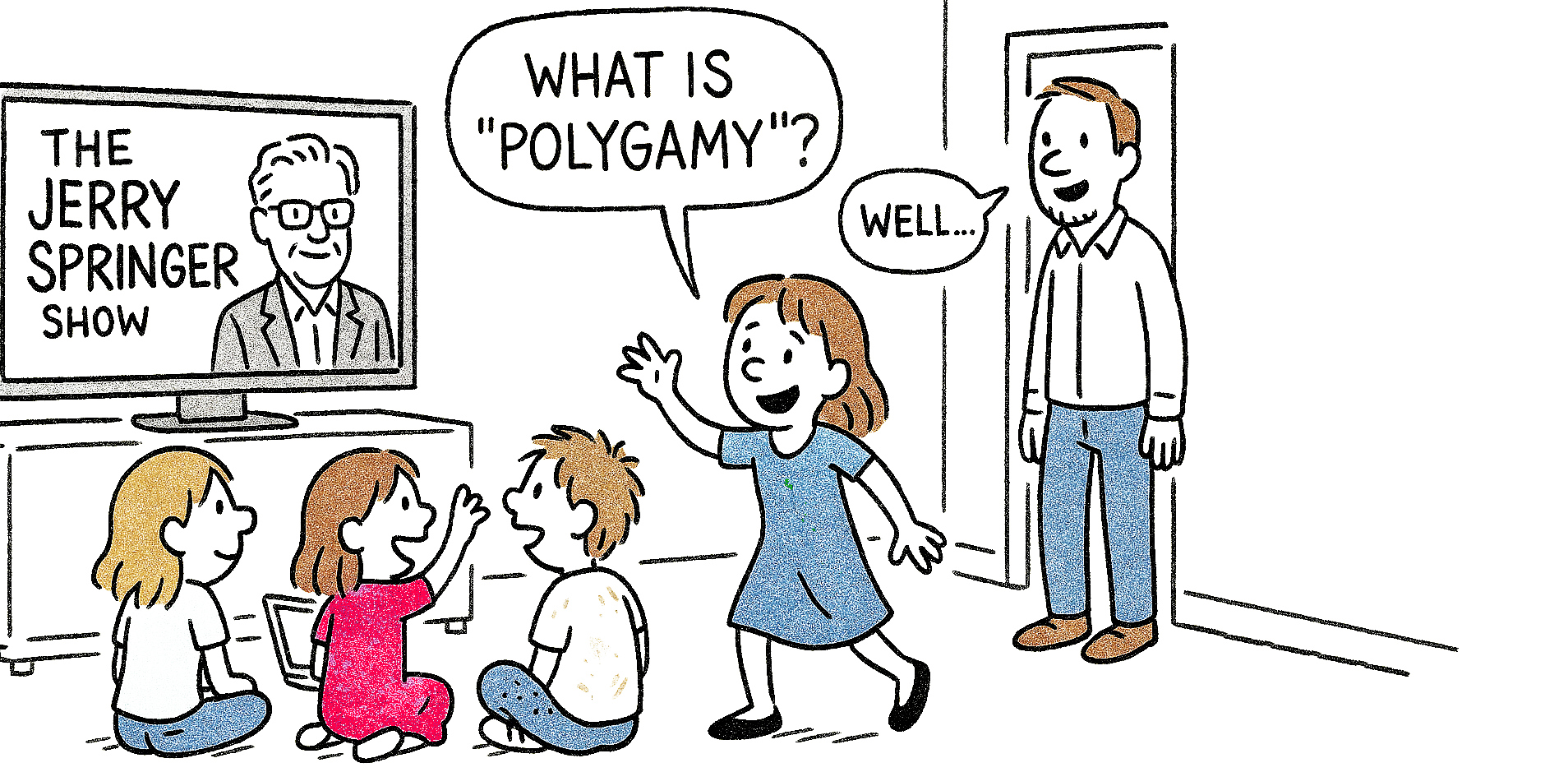

Rather than pointing out all the truly wonderful programmes there are (many of which might not be deemed “educational” by those who limit their children’s access to TV—possibly because they are exciting or interesting or entertaining) I’d like to consider the junkiest of junk TV, Jerry Springer, and with the aid of our real-life example, refute the idea that watching “junk TV” is necessarily a “poor choice” or an “uneducational waste of time”. I watch it myself sometimes, because I do find it very educational myself. I think one can learn a lot from bad theories, and Jerry Springer = bad theories writ large. I have a book case full of bad books on parenting for the same reason. It is useful for critical purposes—for thinking through and understanding why the theories are bad.

“I’m happily surprised that at least two people have had to ask who Jerry Springer is. He is a talk show host—and while most talk show hosts seem to have tried to clean up their act, he still has very sleazy people as guests on his show. Totally inappropriate fare for my children. If someone wants to let their kids watch that, fine, but I’m not about to pay someone to watch my children and have them watch the parade of freaks on that show.”

Even the junkiest of junk television can be superbly educational—by sparking questions and enjoyable conversations.

I have been known to watch Jerry Springer with my children, and it has been very educational for us, in that it has resulted in some deep conversations about important issues. That is to say, during the show, one or other of my children (who may be watching it or may be simply in the same room and happen to see a bit of it) has asked a question or made a comment which has sparked enjoyable, sometimes very lengthy and deep, truly educational conversations in our family.

As a direct result of watching this “sociologically interesting” programme (as a philosopher friend of mine quite seriously describes it), my children and I have had long and fruitful conversations about racism; sexism; the KKK and American history; politics; positive discrimination and its possible psychological and economic effects; price theory and other issues in economics; the second world war; rationing; the holocaust; personal stories of relatives of people we know (how they escaped death at the hands of the Nazis—and many other non-war-related true stories); objective truth; fallibilism; tyranny; “the dogma of otherness” (David Brin’s idea about the Western world’s unique insistence on tolerance/the idea that other ideas/cultures are just as valuable as ours—that it is this very thing that makes Western culture superior to other cultures!); law; moral philosophy; health and nutrition issues; love; friendship; marriage; why people hurt those they love, and why people sometimes can’t get out of or change for the better destructive relationships, despite the fact that most would agree that hurting those one loves won’t help anything; coping strategies; stoicism; inexplicit knowledge; rationality; cosmetic surgery; the idea of women as slaves to physical “beauty”; the history of clothing styles, make-up and hair styles; the idea of the “kept” woman; gender stereotyping—its cause, its effects, etc.; examples of gender-stereotypical behaviour; stereotypical relationships; the evolution of language and English English vs American English; many forms of coercion; conflicting educational theories; cultural phenomena; memes; antirational memes, cults; the psychology of ‘brainwashing’; evolution; religion; the history of Christianity; differences in interpretation of the Bible; polygamy; patriarchy; the meaning of “despotism”; epistemology; authority; rights; bullying; group pressure; alienation; shame; body language and cold reading; gaslighting; the conflicting meanings of “boundaries”; George Orwell’s 1984 and Orwellian language; double binds; freedom; freedom of speech; censorship; autonomy; the difference between “mental illness” and “illness” as in a disease like cancer; the Mental Health Act and sectioning, the meaning of “inculpate”, “exculpate”, “culpable”, Thomas Szasz’s idea of psychiatry qua locking up innocent people and freeing the guilty; the British political system vs the American system; the monarchy; our family history WRT the Second World War, and what it was like for London children like my mother being sent away from the bombing to the country to live with strangers; eugenics; AIDS and sexually-transmitted diseases; other diseases and immunisation; the placebo effect; behaviourism; third world poverty and aid (this might have been sparked by an advertisement rather than the show itself); genetics, genetic abnormalities; medical ethics; abortion—medical aspects and various discussions about moral issues connected with it; discussions about whether it is morally justifiable to have a child (or have it aborted) when you know it will be handicapped or have a short life, etc.; killing, murder, and when it might be right to kill someone; moral dilemmas; game theory; pacifism; conscription; potty training; the meaning of “equivocation”; more on reasoning—explicit discussions about various informal fallacies; logic more generally; meta discussion; heart transplant surgery; … etc., etc.

All these (and many more!) conversations were sparked while watching this junkiest of all junk TV programmes recently—the Jerry Springer Show—and arose out of the children’s own intrinsically-motivated questions. Isn’t that what unschooling is all about? The curriculum-minded may point out that the conversations do not cover every area of the National Curriculum, but luckily, there are other programmes, so that need not worry us too much. 😉

Of course if you are exuding worry or disapproval when your children watch TV, they will be very unlikely to engage you in any wonderfully educational conversations because they will want and need to avoid invoking any further coercion on your part. But in the homes of parents who appreciate TV (even junk TV) TV sparks many incredibly interesting, deep family conversations.

BTW, note that I am not arguing that we should throw out books and reading in favour of TV—far from it. We have about 10,000 books, and have interesting conversations through reading too. But reading is obviously more likely than TV-watching to be a solitary activity, in that if one is reading, no one else gets any information from that unless one relays some to them in some way, or reads to them, whereas with TV, one person might see something in passing or while doing something else, and that might spark a conversation. My children rarely sit down to watch Jerry Springer (they seem quite scathing about it actually); they just see it (or bits of it) during play/other activities in the same room sometimes.

Scott wrote:

“I was one of those who’ve never heard of Jerry Springer before. Given that description I know I wouldn’t watch it twice and probably not very far through the first show I came across. I’m a little surprised, though, at the characterization of people as “freaks.” Are they Not Like Us? Do they believe Weird and Unusual Things? If so, I may qualify as a freak though my kids usually call me silly.”

Er, probably not the Jerry Springer kind, Scott. 😉

See also:

- “Who am I to criticise someone else?”

- “Surely we should communicate our disapproval to our children?”

- What does the UK do about homeschoolers not educating their kids?

Sarah Fitz-Claridge, 1997, ‘How the junkiest of junk tv can be genuinely educational’, https://takingchildrenseriously.com/how-the-junkiest-of-junk-tv-can-be-genuinely-educational