“Tidiness is a thing which is foisted upon children, and it results in all sorts of unpleasant things for them like boredom and having their privacy invaded, and so they get nervous and uptight about their personal space, and sometimes this translates itself into hang-ups about tidiness which they then pass on to their children.”

– David Deutsch

From the archives: First published in Taking Children Seriously 21, 1996: David Deutsch interviewed by Sarah Fitz-Claridge

Many readers will know David Deutsch for his contributions to Taking Children Seriously and to the Taking Children Seriously List [i.e., the email-based discussion forum we used to have], and perhaps as co-author of Home Education and the Law. Some will also know that he is a theoretical physicist who has, among other things, pioneered the new field of quantum computation. There is a major article about his work in the October 1995 Discover magazine (the issue was devoted to “Seven Ideas that could Change the World”). He is often quoted in the media and regularly makes appearances on television and radio programmes. You may have seen his programme on the physics of time travel in BBC 2’s Antenna series. [See also his two life-changing best-selling books: The Fabric of Reality and The Beginning of Infinity]

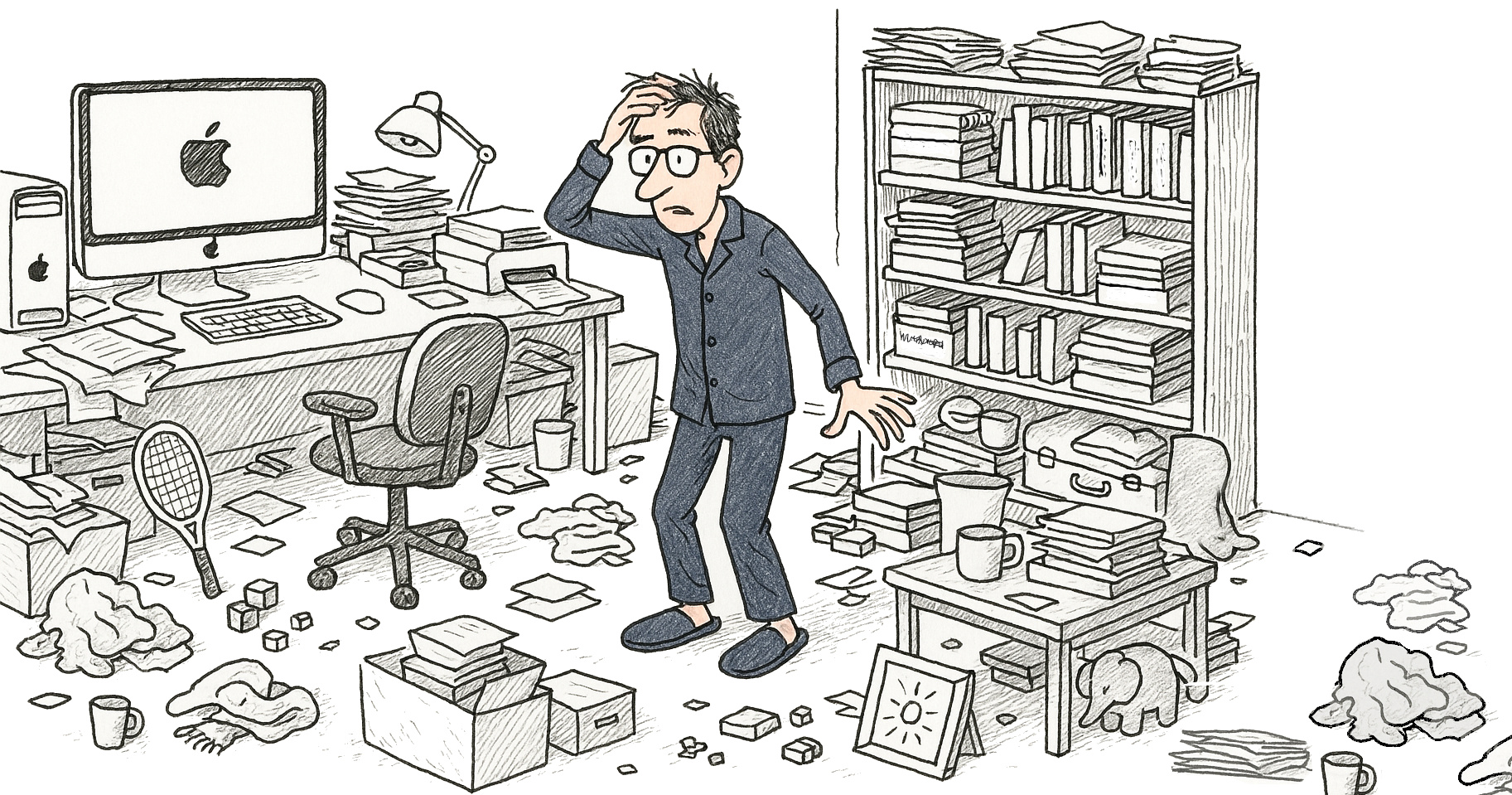

Recently, David was featured in the Channel 4 science documentary series, Reality on the Rocks, in which the actor, Ken Campbell, asked leading scientists about the nature of reality. Those who saw Reality on the Rocks may have caught a glimpse of David’s extraordinarily untidy study, at his home in Oxford. Ken Campbell was so struck by its untidiness that he talks about it in his one-man show, Mystery Bruises. He relates the story of the Japanese film crew who, upon asking to tidy up David’s home before filming there, were told that they could do so, on condition that they returned everything—every piece of paper, every book, every computer disk—to the exact position where it had been on the floor or wherever, and how they did just that!

I put it to David that some might be surprised that someone so untidy could be so successful.

DAVID DEUTSCH: I can’t speak for other people, but in my case, I am fairly sure that I couldn’t be very productive without also being untidy.

SARAH: What makes you think that?

D: It is the style of working that I have always had, from childhood. I chop and change quite suddenly between different problems I am working on. For instance, at the moment I am pursuing several quite diverse projects…

S: What are they, by the way?

D: My biggest single project is writing my book; then there is some research into error correction and several other topics to do with quantum computers. I am writing a short story; I am completing a philosophical paper about parallel universes; I am also writing a computer program to compile concordances of documents. I have just finished writing an article that was inspired by an episode of Star Trek, The Next Generation; I am re-writing two old papers that I abandoned several years ago, one on probability and one on meme theory; and I am translating an old paper of Karl Popper’s from German into English, amongst other things…

Well, anyway, I’ll be sitting at the computer with two or three documents on screen, with the relevant papers and books for that in front of me or on my lap, writing, thinking, making notes, and then, without making a conscious decision to change over, I’ll find that my train of thought goes into one of the other lines. Whereas I was thinking about quantum computation, I’ll go on to thinking about Popper’s conception of objective truth, perhaps. Then I might translate some more of his paper, and then I’ll have a new idea, and so on. Each one of those open lines of thought corresponds to a different set of papers, books and other stuff lying around here—not only in my study but all over my home.

When I go to bed, the resources for all the different lines of thought are left open, some of them in my office, some of them in my bedroom, some elsewhere. I never have to predict when I am finished for the day. I frequently change my mind and work for another five minutes, or another five hours.

By the way, since I work at home, my research can be more integrated with my other interests than perhaps is possible for other people. I also chop and change between what is conventionally called “work” and what is conventionally called “recreation”. I make no distinction between these things. There are no discontinuities in my day. I read novels, play video games, watch television, and so on. Here is a TV guide open amongst the other papers. There is a tennis racket and balls. (I only ever play tennis with people I find interesting to talk to.) There is a note reminding me that I have a meeting with two students tomorrow.

Obviously if I were to tidy each of these things away when I had finished with them, I would not be able to change nearly as often as I do from one train of thought to another, and when I did there would be discontinuities. When I next wanted a particular item, I’d have to go and fetch it from the shelves or filing cabinet or wherever, and that means that there would have to be a gap, during which I would have to know that I had finished doing one thing, and know what I was going to do next.

But in general I don’t know that. Knowing what one is going to think about next is a substantive piece of knowledge about one’s own thought processes, which may not be all that easy to generate, and can be expensive. In my case it is very expensive in both time and effort.

S: What do your colleagues make of your untidy ways?

D: Nothing, really. In my field, untidiness in the working environment is not uncommon. Perhaps most people are not as untidy as I am, but off-hand, I can’t recall many creative physicists who are tidy. One of them was my old boss, John Wheeler. Tidiness is only one of many ways in which he is unusual; perhaps it is connected with another extraordinary thing about him, namely that when he writes out calculations, they are always correct first time, rather as Mozart is said to have written music.

S: So how does Wheeler get round the difficulties that you said would impede your research if you were tidy? Does he only work on one thing at a time?

D: Oh no! Quite the contrary. Now that I come to think of it, I know that Wheeler does have many loose ends open at once, but only in his mind. So his office is tidy only because he doesn’t really use it! But for the rest of us—those whose ideas have to appear on paper and get changed and changed again, set aside and come back to, compared with other ideas, despaired over and dug out again hopefully—in effect our minds exist partly on this paper. Therefore if we have loose ends in our thinking, we must have loose bits of paper.

S: How do you know where to find anything? Don’t you lose things?

D: It is a feature of any filing system, however tidy, that information gets lost in it. That includes the filing system in our minds. Finding things is like picking up a train of thought. Losing things is like losing a train of thought. Yes, I do lose things, but I then I lose much more when I tidy things away.

S: Can you be sure you are not just rationalising this? Could it be that you just hate tidying up?

D: I can’t deny that I hate it! It is a fact that tidying up is boring. There are so many interesting things to do in life that doing boring things is hardly ever top of my list of priorities. The question here is not whether tidiness is boring, but whether it is necessary, or useful. I think that there are no good practical reasons to be anywhere near as tidy as is conventional in our society. Tidiness is a thing which is foisted upon children, and it results in all sorts of unpleasant things for them like boredom and having their privacy invaded, and so they get nervous and uptight about their personal space, and sometimes this translates itself into hang-ups about tidiness which they then pass on to their children.

But where tidiness does have an objective value, I am not opposed to it. There are respects in which I am very tidy.

S: Such as?

D: Well, one of them is folder discipline on my Macintosh. I have strong theories about how documents, applications and so on should be arranged, and I stick to that. It does take a lot of maintenance to do this, but I consider it worthwhile.

I just said that tidying up is boring—but I very much enjoy doing that sort of maintenance. I don’t know what that says about me! I am also very fastidious about fonts and layout and I am quite ready to spend half an hour changing the location of a picture by one millimetre just to get it exactly right; I suppose that that is because there, the tidiness is functional—the tidiness is part of getting my message across.

If I were a surgeon, I would probably be fanatically tidy about my surgical instruments, or about the organisation of my patients’ medical records. But I would be just as untidy as I am now about research papers lying around my office.

S: But in school, children get marks for neatness as well as for content.

D: Yes, unfortunately tidiness is measurable. Creativity isn’t. That shift in focus from substance to form is very antagonistic to creativity because creativity is about substance and not form. If somebody solves an important problem in physics, and gives a research seminar on it, but his slides are very untidy, nobody minds much. If somebody gives a beautiful presentation but has not solved a problem, then it doesn’t matter how beautiful his slides are, people still don’t think much of him.

S: But as a scientist don’t you need to be free of distractions and work methodically?

D: In my experience, scientific progress is never methodical. The answer to the question never comes from the route that one first thinks of. It never comes from even the hundredth route that one would have planned in advance. The conversation one has in the tea room is more important than the seminar that one is ostensibly attending. The paper that one comes across accidentally in the library is more important than the one that one went there to fetch.

Likewise, thinking that the research might be impeded by being ‘distracted’ suggests that there is some correct state of mind that you could be in that is not ‘distracted’—the state of mind which will lead to the answer, as opposed to the ‘distracted’ one, which won’t. But actually, since, as I said, scientific progress is very untidy and involves lots of back-tracking and it often involves going in a direction which one would have initially thought irrelevant, being ‘distracted’ is actually part of the very stuff of discovery, provided that one is distracted by things that seem to make sense.

S: You know, David, if you were a child you’d be deemed to have a short attention span!

D: No doubt. And it would be almost as false for me as it is when said of children. There is no such thing as “attention span”. People, unless they are inhibited by hang-ups or external forces, spend just as long on each topic as they find most conducive to their creative aims. This could mean channel-surfing with five seconds devoted to each channel, or it could mean reading a book for hours at a stretch. I think my own record for attention to one subject was a continuous period of 48 hours when I was completing my work on the quantum physics of time travel.

Surely the important thing about attention is whether it is applied to whatever is right for that person at that time, and what quality of thought accompanies it. Is the insight of a “eureka” moment to be denigrated because, on the face of it, it required only a few seconds of attention? Is a massive tome full of crackpot theories to be highly valued just because some crank spent every waking hour for ten years preparing it?

S: Wouldn’t it help your work to be more tidy? Wouldn’t it help you to know that every day you will sit down and work on such-and-such a piece of research from nine to five?

D: Again, I can’t speak for others but it certainly would not help me. I find that if I have to do something at a fixed time—for instance, I have to give a lecture—then I find myself increasingly unable to work in the period before the lecture, because I am aware in the back of my mind that whatever trains of thought I embark upon cannot be open-ended. This ‘planning blight’ often begins even on the previous day. That’s why I try to arrange my life so that there are as few fixed-time obligations as possible.

S: What if you were forced to be tidy?

D: Hmm. If I were forced to be tidy about, say, keeping reference books on the shelf, then in effect I could not use them. I would not be able to work with them. I suppose I’d have to evolve a different style of work, where I’d be working more within my own mind and less with books and papers. Perhaps that is how Wheeler got to be as he is…

To be forced to be tidy with correspondence would mean that I would become even more lax with it than I am now, and it might well mean that I would answer the letters I don’t really want to, and not answer those I do want to. To be forced to be tidy in general would mean that my work could not be as integrated with my life as it is. That would not be a fatal restriction, but it would reduce my productivity. What I would probably do is have an inner sanctum—a study or something—which remained untidy, whilst the rest of the house was tidy. That would mean I couldn’t be working on a paper while I was in bed, and I could not be writing a referee report while having dinner, and so I’d have less opportunity for work.

S: What about self-discipline. At school we were always told that we’d never amount to anything without self-discipline, in other words, if we failed to be tidy in our work.

D: That isn’t self-discipline. That is obedience. Real self-discipline is important in creative thinking. That is, one has to learn to allocate one’s mental and other resources in a way that promotes one’s own values, rather than in some other way, perhaps in a thoughtless way, or in a way which promotes someone else’s values. This is not something one can do just by following some fixed rules of tidiness; it is something one is learning throughout one’s life, and if, as is customary, one does not learn to do this in childhood, then whenever one begins creative work, one has to relearn this self-discipline in the right sense.

Creativity involves a combination of fanatical attention to detail, and open-ended chaos. One cannot tell which issues are going to be which: it is whatever arises out of the needs of the problem. For me, it is necessary to keep the inside of my computer in meticulous working order, more meticulous, by the way, than any parent or teacher could ever require of me, because the organisational rules I adhere to are too complicated to be easily checked.

S: What do you think one can do to help a child develop self-discipline in the right sense, in the sense you speak of, in regard to tidiness/untidiness issues and more widely?

D: Perhaps the most important thing is to make sure that the child has a space which is exclusively under his control. Then one should try hard not to have a preconception about what should be tidy and what should not be tidy—and what counts as “tidy”. Another thing is to encourage the child to form preferences about his environment and to help him act on them. For instance, honour his preferences about his space—what colour the walls are, whether there is a desk, or a box for the toys, and so on. Forming complex preferences about the use of one’s environment is necessary for creativity.

Let me put that another way. As I have said, a scientist’s study—with its papers and other resources in a certain configuration—is an extension of his mind. So just as academic freedom is necessary for progress in science, freedom of thought in the wider sense—including the freedom to dispose one’s working environment in the way one chooses—is equally essential.

Children’s lives and ‘work’ are automatically integrated (except when forcibly separated by school and suchlike), because their lives consist of learning. So if you intrude into their bedroom, which is usually the only private space they have, you are intruding into their minds. Then they will not be able to learn to use that space creatively, and the development of their creativity will be disabled.

Being forced to enact someone else’s idea about the disposition of one’s working environment is tantamount to enacting someone else’s idea of what one’s mind should be. Some people’s view of education is precisely that—that one is making the child’s mind into what one thinks it ought to be. But if that were the case, there would never be any progress, because children would be just like their parents, and students would be just like their professors. The best professors that I have known—in the sense of the ones who have the most brilliant students—allow their students to set the agenda not only in terms of the subject matter being studied, but of the method by which it is studied, including whether the student works at home or in the lab. The ones who rigidly control their students tend to produce students who contribute to the professor’s own projects but never make it in their own right.

[Some readers might like to see what David said when asked by an interviewer about the mess in David’s house. David’s answer begins ~16:35 minutes into this video.]

See also:

- “What does education taking children seriously look like?”

- “Will a child not made to do chores ever develop a work ethic? And if not, how will they ever have a good life?”

- “Does Taking Children Seriously mean children always getting their own way?”

Sarah Fitz-Claridge interviews David Deutsch, 1996, ‘Creativity and untidiness’, Taking Children Seriously 21, ISSN 1351-5381, pp. 6-10, https://takingchildrenseriously.com/creativity-and-untidiness/

1 thought on “Creativity and untidiness”

Comments are closed.