“To avoid being part of an adult conspiracy against a child when you are a bystander, let the child know you disagree with what the parent is doing. Or maybe you can find a way to touch the parent’s heart and bring parent and child together.”

– Sarah Fitz-Claridge

From the archives: Posted on 29th August 1997

Barbara wrote:

“While I was at the aquarium with the kids on vacation, an incident happened that greatly disturbed me. I wanted your feedback in the hopes that I can respond better if such a thing happens again. I had entered the restroom (dh was with the children) and was in the stall when I heard a women enter with a crying child. She brought her into the stall close to mine. The women was shouting angrily ‘Stop it! Stop it! right now!’ to the child who continued to cry. As I left the stall, I heard a loud ‘smack! smack!’. I started towards the stall she was in and she burst out dragging a small crying child in one hand and a wide belt in the other. I looked at the child with sympathy; she looked back at me for help I felt which I felt so inadequate to give. The incident disturbed me greatly and I felt as if I had let the poor child down.”

The same thing happened to me once—well—not quite so extreme, but an extremely angry man smacked and shouted at a child near me in a shopping mall. I wanted to do something or say something, but the fear of this man’s potentially violent reaction stopped me. At least—that is how it seemed to me at the time. Like you, I felt that I had done the wrong thing—let the child down. After that incident, I thought about what to do if something like that were to happen again, and came up with my own answer, which has helped me to be true to myself since then.

These incidents are repugnant for obvious reasons—the violence, the pain, the sheer irrationality of it all. But what is particularly disturbing for me, at any rate, is the element of being drawn in to an adult conspiracy against the child. That is to say, bystanders are expected to pretend to see nothing. It isn’t just that bystanders fear violent reactions; there is a taboo against getting involved. Barbara ‘interrupted’ the ‘discipline’ and should have ‘minded her own business’. Well yes, all right, I can go along with the idea of minding my own business, where that is what we are talking about. But in these cases where I am a bystander, a witness, that is not what we are talking about. At such times, especially if the child knows I am there, it becomes my business, because there is no possible neutral response. There is no such thing as not being involved.

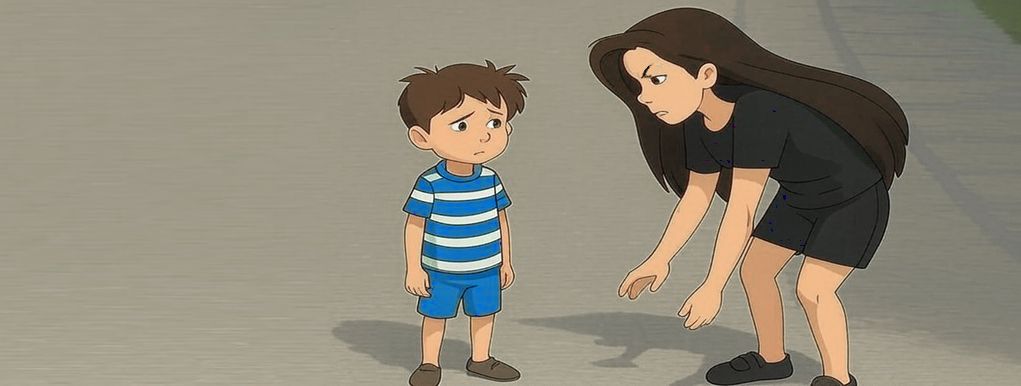

If you are there when a person is being badly treated, you are involved. If you do nothing (‘don’t get involved’) the message you send to the child is not no message, but the message that what is happening to him is acceptable; that you agree with it. There is no getting away from this. Either you let the child know that you most certainly do not approve of what is happening to him, or you effectively tell him you agree with what is happening.

So… after that particular incident in the shopping mall eight years ago, I made a conscious decision that from then on, I would never betray another child by ‘not getting involved.’ I would never again allow myself to become part of an adult conspiracy against a child. I decided that from then on, I would be true to my own values, and always do something to let the child know that I totally disapprove of the adult’s actions. It doesn’t have to be much.

I don’t talk to young children I don’t know, for obvious reasons. But I do make a point of giving the child the information that I disapprove of the adult’s actions any way I can that isn’t going to scare the child or whatever. When I am with others, I will give my opinion to my friends loudly in words, throwing withering looks at the adult. When children are with me, they tend to say things in loud voices and instead of shushing them as others might, I agree and say what I think too.

If the child is older (and thus less likely to feel threatened by me) I occasionally say (from a non-threatening distance), “I don’t think she should be doing that to you/treating you like that.” When it is a child we know, I say directly to the child “You know I think this is beastly, don’t you? Look I can’t make him stop this, but would you like me to try to talk him out of it? Is there anything else I can do?” Sometimes I say to the parent, “Oh please don’t. Please don’t do this to her.” (That is when I am aghast and find it too painful to watch.)

With really intimidating men, when I fear for my personal safety if I intervene, it is still possible to stop, give a withering stare (from a bit of a distance) and somehow let the child know I disapprove.

If I were to hear a child being beaten in the lavatory, I’d make a point of saying something like “She must know that hitting a child is wrong, or else she would do it openly. Isn’t that despicable?”

Before anyone gets the wrong idea, the point of this is never to shame the adult into better behaviour. No one learns through being shamed. The sole point of this is to give the child the information that someone in the world—another adult—disagrees wholeheartedly with the treatment the child is receiving.

I have found that it gets easier every time.

Won’t this make the adult mistreat the child even more? First, remember the ‘consistency’ principle—the ‘united front’ principle—the taboo against ‘undermining parental authority’? All these things are about making the coercion of the child more effective psychologically. Giving the child the information that you disagree directly sabotages these things, and is thus incredibly valuable for the child. Indeed, the psychological benefit the child will gain from knowing that at least one adult strongly disapproves dramatically outweighs any extra harsh treatment he may get as a result of the incident. But actually, I don’t believe it. It isn’t true that children get extra harsh treatment as a result. The parent will just continue exactly as before.

I imagine some Americans are going to reply that there is a risk of getting shot. I don’t doubt that there is such a risk, just as here, one might get knifed. That alters nothing. It is still possible, through oblique comments and dirty looks, to intervene to get the information across to the child in a non-threatening manner.

Doing nothing can, in some circumstances, make you morally culpable. The film, The Accused, is worth watching in this connection.

Note added 2025:

I still agree with that decision I made 36 years ago, never again to allow myself to be drawn in to an adult conspiracy against a child. But one slight modification to my policy is that I am now much more optimistic about my ability to make a positive difference in such moments.

My aim is not just to give the child the all-important information that I disagree with the parent’s behaviour, but also—if at all possible—to melt the parent’s heart rather than hardening it, to show the parent how amazing their child is, and to bring parent and child together. I assume the best about the parent despite what they are doing, just as it is lovely when parents can find it in their hearts to assume the best about their children despite what their children may be doing.

Maybe the parent is behaving badly because they are dealing with an unrelated catastrophe in their life, or maybe someone humiliated them on the internet earlier and they are feeling deeply wounded, or maybe they are about to be evicted, or they have just lost their job, or their partner is suddenly very ill and they are scared, or maybe they are worrying about how they are going to manage to navigate the draconian new anti-home-education law given that the last thing they want to do is to force their unwilling children to go to school. Or maybe they are trying to do what their fire and brimstone pastor has told them is necessary to save their child’s immortal soul, and every fibre of their being is crying out against treating their beloved child that way.

It is perfectly possible to convey to the child the information that I think what the parent is doing or has just done is wrong, without demonising the parent as evil or giving the child the impression that I think people (such as the parent) should be punished for behaving badly.

Good people sometimes do the wrong thing. Conveying that only evil people do the wrong thing would be a life-blighting message to give a child. So is conveying the idea that people are improved by punishment. People make mistakes including moral ones. And mistakes can be corrected. But not by punishment from without. Only by the person from within.

No one wants to be at odds with their child. You can facilitate their reconnection. You can show them the other’s goodness that they have lost sight of. And you can show them their own goodness that they have lost sight of. Often I see the stress and anger melting away, replaced by lovingkindness and connection.

See also:

- Unnatural consequences revisited

- Expressing approval vs expressing appreciation

- Criticism of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

Sarah Fitz-Claridge, 1997, ‘Be a bystander who makes a difference’, https://takingchildrenseriously.com/be-a-bystander-who-makes-a-difference