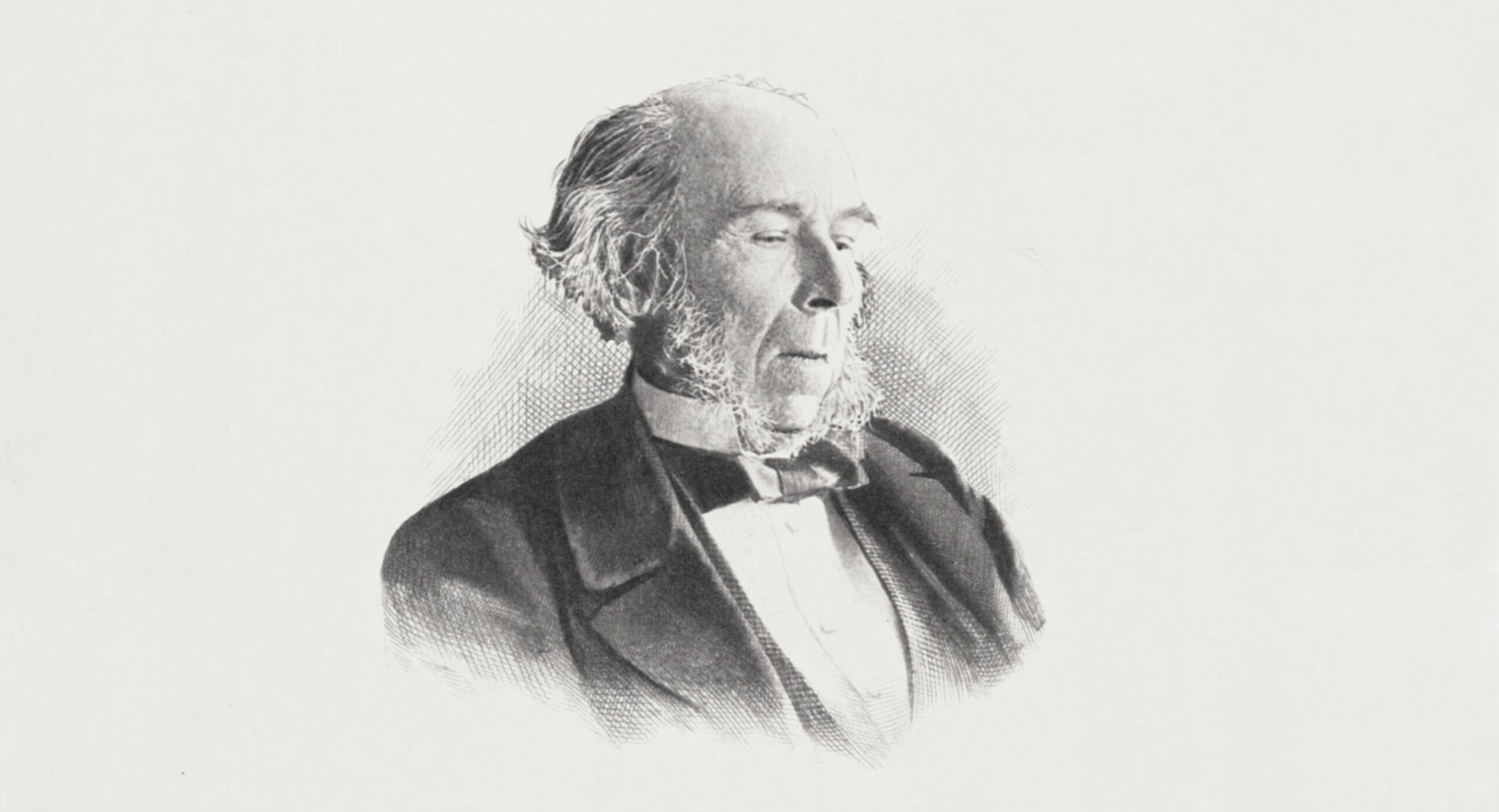

“The first person I know of who advocated that children have equal rights with adults was Herbert Spencer. In his Social Statics, written in 1850, Spencer boldly states that every child ‘has claims to freedom—rights, as we call them—coextensive with those of the adult.’”

– Ken K.

From the archives: Posted on 19th October, 1995

The first person I know of who advocated that children have equal rights with adults was Herbert Spencer. In his Social Statics, written in 1850, Spencer boldly states that every child “has claims to freedom—rights, as we call them—coextensive with those of the adult.” What did Spencer mean by this? He meant that children have the same entitlements and obligations as adults with regard to the “law of equal freedom”, i.e. that “every man has freedom to do all that he wills, provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man”. Spencer went on to explicitly state that by “man” he also meant to “include under it both sexes and all ages.”

This was quite a revolutionary declaration! Up until that time virtually nobody considered children as having the same rights as adults. Indeed, the conventional wisdom was that children were either the property of the state or vassals of their parents. In The Laws Plato claimed that children “belong to the state first and their parents second.” Aristotle, who was often at odds with his mentor, agreed with him on this issue, saying in Politica that children “all belong to the state.” In subsequent years, from the Greeks to the Romans, through the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, the question was always “who should control the child, the parents or the state?” Never during this period was it considered for a moment that the child had any “rights” of his own.

It wasn’t until the seventeenth century that the child’s plight began to brighten. John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education at least began to question the absolute authority that parents and the state had hitherto wielded over the young. Although he never spelled out exactly what rights a child had, he denied that fathers had by divine right the power of life and death over their children. This was at least a beginning.

Unfortunately, with the eighteenth century Enlightenment came also the rise of nationalism—and with it the idea that the interests of the state supersede those of the individual. Rousseau argued in The Social Contract that the state should not “abandon to the intelligence and prejudices of fathers the education of their children, as that education is of still greater importance to the state than to the fathers.” With the advent of the French Revolution, we have Danton proclaiming, “The time has come to establish the principle that children belong to the Republic before they belong to their parents.” By 1793 the National Convention declared that primary education in the Republic would be free and compulsory and that prospective teachers had to possess a “certificate of patriotism and morality.” This was the beginning of the modern nation state—which didn’t bode well for children.

G. W. F. Hegel championed the state over the individual, especially over young individuals. For Hegel, the purpose of education was “to break down the child’s self-will” and like Rousseau before him, he believed that “society’s right here is paramount over the arbitrary and contingent preferences of parents.”

It was in this setting that Spencer launched his revolutionary idea that children were not to be forced to do anything … either by parents or the state! He flatly called parents who coerce their children “vicious”. It was Spencer who first looked upon children as individuals with legitimate rights of their own, not to be trampled on by either parents or the state. Spencer viewed children as autonomous human beings and objected to any infringement of their rights because of their dependency on adults. With impeccable logic, he deduces that children must have the same rights as adults—and I commend to you this beautiful demonstration, which can be found in Chapter 17 of Social Statics. (Unfortunately it is based on the dubious premise that “God wills human happiness”).

Still, Spencer’s ideas on children’s rights deserve wider circulation. I propose to do just that by concluding this post with an extended quotation from the chapter entitled “The Rights of Children” in Social Statics :

“Those, therefore, who advocate the use of authority—and, if need be, force—in the management of children, must do so because they think these the best means of compassing the desired object—formation of character. Paternity has to devise some kind of rule for the nursery. Impelled partly by the creed, partly by custom, partly by inclination, paternity decides in favor of a pure despotism, proclaims its word the supreme law, anathematizes disobedience, and exhibits the rod as the final arbiter in all disputes. […] Suppose, now, we inquire how the plan works. An unamiable little urchin, in pursuing his own gratification regardless of the comfort of others, is perhaps annoyingly vociferous in his play, or is amusing himself by teasing a companion; or is trying to monopolize the toys intended for others in common with himself. Well some kind of interposition is manifestly called for. Paternity, with knit brows and in a severe tone, commands desistance; visits anything like reluctant submission with a sharp “Do as I bid you”; if need be, hints at a whipping or the black hole—in short, carries coercion or the threat of coercion far enough to produce obedience. After sundry exhibitions of perverse feeling, the child gives in; showing, however, by its sullenness the animosity it entertains. Meanwhile paternity pokes the fire and complacently resumes the newspaper under the impression that all is as it should be: most unfortunate mistake!

If the thing wanted had been the mere repression of noise or the mechanical transfer of a plaything, perhaps no better course could have been pursued. Had it been of no consequence under what impulse the child acted, so long as it fulfilled a given mandate, nothing would remain to be said. But something else was needed. Character was the thing to be changed rather than conduct. It was not the deeds but the feeling from which the deeds sprang that required dealing with. Here were palpable manifestations of selfishness—an indifference to the wishes of others, a marked desire to tyrannize, an endeavor to engross benefits intended for all—in short, here were exhibitions of a small scale of that unsympathetic nature to which our social evils are mainly attributable. What, then, was the thing wanted? Evidently an alteration in the child’s disposition. What was the problem to be solved? Clearly to generate a state of mind which, had it previously existed, would have prevented the offending actions. What was the final end to be achieved? Unquestionably the formation of a character which should spontaneously produce greater generosity of conduct.

[…] Observe, then, how the case stands. A grasping, hard-natured boy is to be humanized—is to have whatever germ of better spirit may be in him developed; and to this end it is proposed to use frowns, threats, and the stick! To stimulate that faculty which originates our regard for the happiness of others, we are told to inflict pain or the fear of pain! The problem is—to generate in a child’s mind a sympathetic feeling; and the answer is—beat it or send it supperless to bed!

Thus we have but to reduce the subjection theory to a definite form to render its absurdity self-evident. Contrasting the means to be employed with the work to be done, we are at once struck with their utter unfitness. Instead of creating a new internal state which shall exhibit itself in better deeds, coercion can manifestly do nothing but forcibly mold externals into a coarse semblance of such a state. In the family, as in society, it can simply restrain; it cannot educate. Just as the recollection of Bridewell and the dread of a policeman, while they serve to check the thief’s depredations, effect no change in his morals, so, although a father’s threats may produce in a child a certain outside conformity with rectitude, they cannot generate any real attachment to it. As someone has well said, the utmost that severity can do is to make hypocrites; it can never make converts.”– Herbert Spencer, 1851, Social Statics, Part II, Chapter 17: The Rights of Children, §4, pp. 181-183

See also:

- With coercive relatives stay calm and quietly uphold the child’s rights

- Rediscovering my joy as my children follow theirs

- Reacting to an angry child

Ken K., 1995, ‘Herbert Spencer on children’s rights’, https://takingchildrenseriously.com/herbert-spencer-on-childrens-rights/